Video Link: https://vimeo.com/290600362

Video Download: Click Here To Download Video

Video Stream: Click Here To Stream Video

Video Link: https://vimeo.com/290600941

Video Download: Click Here To Download Video

Video Stream: Click Here To Stream Video

After Testosterone Blast of Hunting, Men’s ‘Love Hormone’ Rises When They Return Home

Testosterone. It fuels the drive of hunters, athletes, traders in the financial markets and other so-called “Alpha males.”

And regardless of their differences,  they all tend to have one thing in common: they are all ultra-competitive and possess an almost superhuman drive to succeed.

they all tend to have one thing in common: they are all ultra-competitive and possess an almost superhuman drive to succeed.

As a result of this drive, their testosterone levels are off-the-charts, primarily when they are engaged in the high-level competition of their brutally Darwinist fields.

But There is Another Side to This Story

The Chinese call it Yin/Yang.

In Viking times, it was called Fire/Ice.

The ancient Greeks called it “The Golden Mean.”

Regardless of the name, the fundamental concept remains the same today: balance, including mental, physical, and emotional aspects, is something that we all need and strive for, at times unconsciously.

And it is just as relevant today as it was thousands of years ago.

Fascinating New Research

A new study explores the nurturing, familial side of men who pursue primal activities, often to support their families.

It finds that that side, too, is expressed hormonally when a man brings dinner home to his family (or perhaps money or a trophy).

The results of the study were surprising and a bit unexpected.

The results of the study were surprising and a bit unexpected.

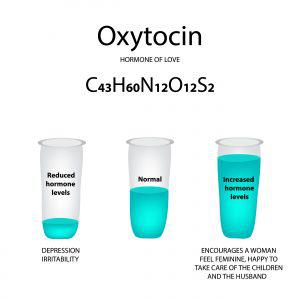

Researchers have found that the more a man’s testosterone has risen in his choice of hardcore male activity, the more the “love hormone” oxytocin tends to surge upon coming home.

The researchers additionally discovered that the longer his workday, the higher his oxytocin levels are when he returns to his family.

Previous studies have shown that oxytocin makes people more cooperative, while testosterone has the opposite effect.

That finding, one of the first to measure oxytocin release in a naturalistic setting, emerged after anthropologists from the University of California, Santa Barbara, shadowed male members of an Amerindian tribe in the Amazon Basin of Bolivia as they hunted for food.

To conduct the study, UCSB anthropologist Benjamin C. Trumble joined the hunters as they went out into the jungle and attempted to make a kill to feed their families.

The 31 men studied were members of the Tsimane hunter-gatherer tribe of Bolivia.

Trumble collected salivary samples (spit) from the hunters, first as they departed on their day-long and often solitary hunts; again after their first chance to bag a prey animal; and finally, shortly after they returned home.

The oxytocin was measured in the UCSB Human Biodemography Laboratory.

Published in the Royal Society’s Biology Letters, the resulting findings discovered (much to their surprise) that men whose “day job” drove their testosterone highest also experienced the highest levels of oxytocin when they came home.

The team also found that high testosterone levels while hunting could be attributed to a "winner effect" experienced by men making a kill.

The increased oxytocin could serve as a balance to make the hunters kinder, more generous, and more willing to share their bounty.

At first glance, this does indeed seem strange.

Testosterone and oxytocin are antagonistic, said UCSB anthropologist Adrian V. Jaeggi, co-lead author: Though high testosterone levels are usually associated with aggressive, drive-for-dominance behavior, bursts of oxytocin are linked to sharing, cooperation, trust , and tenderness.

, and tenderness.

'Our goal was to look at the interaction between different hormones in motivating behavior in a naturalistic context,' said Jaeggi.

'Hunting for subsistence and sharing meat is something people have done for hundreds of thousands of years.'

The needs of the social group may demand that a man who has demonstrated aggression all day find a way to reintegrate with his kin and share his food.

The release of the hormone oxytocin may serve precisely to help in that transition, or to signal that the returned hunter has successfully shifted roles, said Jaeggi.

“Testosterone, whatever the reason for the increase, is liable to make you more asocial, and that might not be a good thing when you’re coming home to your family and community,” Jaeggi said.

“Oxytocin, on the other hand, makes you more empathetic, which would be useful in a social context.”

Restoring Physical Balance as Well as Emotional Balance

Both hormones may play another role for returning hunters: After the physical exertions of the hunt, testosterone and oxytocin also have been shown to assist in rebuilding muscle.

That tonic effect may be purely coincidence, or it may have been the hormonal influence that helped men form bonds with their partners and children in early human societies.

"These men are coming home, they're finished with work for the day, and they're about to eat and share food," Jaeggi continued.

"So the need to be social coincides with the need to regenerate, and it would make sense for the same hormones to facilitate both functions."

Jaeggi anticipated a conflict between the two hormones and was surprised to find a beneficial relationship.

As mentioned earlier, Jaeggi and co-author Trumble feel that high testosterone while hunting could be attributed to a 'winner effect' experienced by men after a successful hunt.

As mentioned earlier, Jaeggi and co-author Trumble feel that high testosterone while hunting could be attributed to a 'winner effect' experienced by men after a successful hunt.

It could also be related to the awards that successful hunting represents for traditional societies such as the Tsimane.

The oxytocin boost could balance the hunter's aggression to make the hunter kinder and more generous.

'Almost half a century ago, it was famously documented that successful Kung hunters were jokingly insulted by others to 'cool their hearts' to 'make (them) gentle,' lest pride or boasting disrupt the egalitarian social system common to many foragers,' said senior co-author Michael Gurven.

'Here we observe a potential hormonal analog consistent with the type of leveling behavior seen in hunter-gatherer societies.'

The latest study on oxytocin sharply contrasts to a plethora of new research on the hormone.

This study measured oxytocin in circulating blood (not in the brain, where it may do its heaviest lifting) in a natural setting. But many other studies have puffed solutions of oxytocin up the nose to see how and if an increase would affect behavior.

Both methods seem to agree that oxytocin has probably played an influential role in the evolution of humans’ social bonds.

Jaeggi said the finding that a long absence from home was linked to higher oxytocin levels upon return suggested the notion that absence makes the heart grow fonder could be a universal human experience.

“Reconnecting with their families after a day of separation would have been a pervasive challenge for men throughout evolutionary history, and oxytocin could help with that.”

Who are the Tsimane People?

The study was based on the Tsimane people, an indigenous population of forager farmers and hunters living in the lowlands of Bolivia's Amazon basin.

Researchers claim the human hormone system is particularly well adapted to their lifestyle, which revolves around small, tight-knit communities.

Jaeggi stated that though the sample size is 'not enormous, the study 'definitely adds to the current literature in which the interplay between testosterone and oxytocin is often overlooked.'

There's No Place Like Home

So how do these observations apply to our modern society? "I think the 'absence makes the heart grow fonder' effect could potentially be prevalent," said Jaeggi.

"Reconnecting with their families after a day of separation would have been a widespread challenge for men throughout evolutionary history, and oxytocin could help with that."

Additional research on oxytocin has shown its ability to form deep personal relationships. "Oxytocin levels indicate how much you value another person," said Jaeggi. "It's a physiological measure of the value of that relationship."

For example, when you love someone, your oxytocin level will soar when you're with them.

"Even talking to someone on the phone is enough to cause that oxytocin increase," he continued.

Men are not the only ones who enjoy the benefits of oxytocin.

"Like the biology of most social behaviors, it originated in the mother-infant context, where it facilitates giving birth, nursing, and bonding," Jaeggi explained.

"It is found in all mammals, and it then got used in other contexts in some species."

One finding that surprised the researchers involved the link between social variables and oxytocin increase: There was none.

"I would have expected that men who have more children experience a greater increase when they come home because they're about to see their families," said Jaeggi.

"Or the guys who encounter people on the way home and get to show off their hunting skills...none of these things affected the oxytocin change. The magnitude of the increase didn't differ about these social variables."

Another exciting correlation, Trumble noted, is that the average Tsimane hunt lasts eight and a half hours, roughly equivalent to a workday here.

Though the sample size is "not huge," he and Jaeggi noted, the study "definitely adds to the current literature in which the interplay between testosterone and oxytocin is often overlooked."

More than anything else, the sample size is a function of the cost of the lab assays needed to measure the oxytocin.

"One of our plans is to develop our assay to make it less expensive so we can analyze much larger samples," Jaeggi said.

The Studies Will Continue

Jaeggi and Trumble mentioned that a significant problem with their research is that oxytocin has two different release systems:  one in the brain and another in the rest of the body.

one in the brain and another in the rest of the body.

This results in their measure of oxytocin circulating in the blood not corresponding to levels in the brain.

"Some of the social effects of oxytocin might be happening in the brain, and we aren't necessarily capturing that with the saliva sample," Jaeggi explained.

"Of course in this kind of study, all we can do is measure peripheral oxytocin. Measuring oxytocin in the brain would be highly invasive."

According to Trumble, oxytocin studies in the U.S. often use nasal sprays to administer the hormone.

"There's a set of tissues right where arteries meet the brain called the blood-brain barrier. Any molecule above a certain size can't pass through it," he explained.

"But there's a weakness in the blood-brain barrier in the nasal canal and allows some transfer to occur. So many experimental studies of oxytocin don't measure oxytocin levels at all, but instead, administer oxytocin and examine before-and-after changes in behavior."

The researchers emphasized that one significant variable adds validity to their work: their ability to study the endogenous levels that are changing naturally rather than from pharmaceutical chemicals.

"With the nasal spray, people are getting colossal concentrations of oxytocin; it can increase their circulating levels to over 100 times the normal physiological levels," Jaeggi said.

"And if there's a change in behavior, it's not the body itself that's producing the changes."

Just as critical is their focus on the interaction of the two hormones.

"Most researchers tend to look at oxytocin or testosterone one at a time," Trumble said.

"But the endocrine system is complex and interconnected, so understanding how changes in testosterone impacts oxytocin and vice-versa is vital."

As observations such as those in this study become more affordable and frequent in scientific literature, researchers will be closer to discovering some of the secrets of the brain and human behavior in ways not previously imaginable, especially with the current model of studying one hormone at a time.

"One of the keys to the future of really understanding human behavior is going to be looking at a whole host of hormones together, all at the same time," Trumble said, "and starting to understand those complicated interactions.

Absence, it seems, really does make the heart grow fonder.

Reference

UCSB anthropologists study testosterone spikes in non-competitive activities

Contact Us Today For A Free Consultation

- Adverse Effects of Testosterone Therapy in Adult Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis [Last Updated On: July 2nd, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 4th, 2010]

- Low Testosterone Levels, Foods That Increase Testosterone Levels wwwSelf-Improvement-Bible.com [Last Updated On: November 12th, 2023] [Originally Added On: May 30th, 2011]

- Low Testosterone in Men: The Next Big Thing in Medicine! - Abraham Morgentaler, MD [Last Updated On: May 7th, 2023] [Originally Added On: June 3rd, 2011]

- How To Determine Testosterone Levels By Looking At Your Ring Finger [Last Updated On: December 7th, 2017] [Originally Added On: June 30th, 2011]

- Prolab Horny Goat Weed Testosterone Booster Supplement Review [Last Updated On: November 23rd, 2023] [Originally Added On: July 19th, 2011]

- The Healthy Skeptic: Products make testosterone claims [Last Updated On: August 13th, 2024] [Originally Added On: September 11th, 2011]

- How To Naturally Increase Testosterone [Last Updated On: November 21st, 2023] [Originally Added On: September 28th, 2011]

- Testosterone Production - Video [Last Updated On: November 25th, 2024] [Originally Added On: November 20th, 2011]

- Testosterone makes us less cooperative and more egocentric, study finds [Last Updated On: January 23rd, 2018] [Originally Added On: February 1st, 2012]

- Testosterone makes us less cooperative and more egocentric [Last Updated On: January 24th, 2018] [Originally Added On: February 1st, 2012]

- Too much testosterone makes for bad decisions, tests show [Last Updated On: April 30th, 2025] [Originally Added On: February 1st, 2012]

- Today in Research: Testosterone's Negative Effects; Diet Soda Death [Last Updated On: January 2nd, 2018] [Originally Added On: February 2nd, 2012]

- Testosterone drives ego, trips cooperation [Last Updated On: December 2nd, 2017] [Originally Added On: February 4th, 2012]

- FDA approves BioSante/Teva's testosterone gel [Last Updated On: April 28th, 2025] [Originally Added On: February 15th, 2012]

- 'Manly' Fingers Make For Strong Jawline in Young Boys [Last Updated On: December 1st, 2017] [Originally Added On: February 15th, 2012]

- Teva, BioSante Win U.S. Approval for Testosterone Therapy [Last Updated On: December 10th, 2017] [Originally Added On: February 15th, 2012]

- BioSante Gains on Approval of Testosterone Gel: Chicago Mover [Last Updated On: January 8th, 2018] [Originally Added On: February 16th, 2012]

- BioSante soars following drug approval from FDA [Last Updated On: December 26th, 2017] [Originally Added On: February 16th, 2012]

- Antibodies, Not Hard Bodies: The Real Reason Women Drool Over Brad Pitt [Last Updated On: December 24th, 2017] [Originally Added On: February 21st, 2012]

- Almark Publishing Releases Book From Mark Rosenberg, M.D. Revealing Natural Discoveries Associated With Low ... [Last Updated On: May 3rd, 2025] [Originally Added On: February 28th, 2012]

- Testosterone Replacement Clinic Comes to Kansas City with Potential to Help Thousands of Men [Last Updated On: May 2nd, 2025] [Originally Added On: March 1st, 2012]

- Study examines the relative roles of testosterone and its metabolite, dihydrotestosterone in men [Last Updated On: December 2nd, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 7th, 2012]

- The Role of 5{alpha}-Reductase Inhibition in Men Receiving Testosterone Replacement Therapy [Editorial] [Last Updated On: December 21st, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 7th, 2012]

- Effect of Testosterone Supplementation With and Without a Dual 5{alpha}-Reductase Inhibitor on Fat-Free Mass in Men ... [Last Updated On: January 3rd, 2018] [Originally Added On: March 7th, 2012]

- Why We Like Men Who Can Keep Their Cool [Last Updated On: December 30th, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 7th, 2012]

- Testosterone And Heart Health [Last Updated On: May 1st, 2025] [Originally Added On: March 10th, 2012]

- Your Life on Testosterone: Overly Sure of Yourself, Unwilling to Listen [Last Updated On: November 25th, 2018] [Originally Added On: March 15th, 2012]

- Mayo Clinic-TGen study role testosterone may play in triple negative breast cancer [Last Updated On: December 8th, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 23rd, 2012]

- A dose of testosterone might not cure what ails you [Last Updated On: January 23rd, 2018] [Originally Added On: March 25th, 2012]

- Green tea could aid athletes hide testosterone doping [Last Updated On: December 16th, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 25th, 2012]

- TGen Study Role Testosterone May Play in Triple Negative Breast Cancer [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 26th, 2012]

- Testosterone low, but responsive to competition, in Amazonian tribe [Last Updated On: January 23rd, 2018] [Originally Added On: March 28th, 2012]

- Competition-linked bursts of testosterone are fundamental aspect of human biology, study of Amazonian tribe suggests [Last Updated On: December 25th, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 28th, 2012]

- Playing football boosts testosterone levels by 30 percent! [Last Updated On: February 4th, 2024] [Originally Added On: March 28th, 2012]

- Testosterone low, but responsive to competition, in Amazonian tribe -- with slideshow [Last Updated On: December 9th, 2017] [Originally Added On: March 28th, 2012]

- The benefits of testosterone pellet therapy [Last Updated On: January 24th, 2018] [Originally Added On: March 29th, 2012]

- Low testosterone levels cause health woes [Last Updated On: November 25th, 2018] [Originally Added On: March 30th, 2012]

- Heart Failure Patients Getting Relief from Testosterone Supplements [Last Updated On: May 5th, 2025] [Originally Added On: April 21st, 2012]

- Study Finds Fatherhood Suppresses Testosterone [Last Updated On: May 4th, 2025] [Originally Added On: May 3rd, 2012]

- Low testosterone levels could raise diabetes risk for men [Last Updated On: January 26th, 2018] [Originally Added On: May 5th, 2012]

- Why low testosterone may increase your risk of diabetes [Last Updated On: November 25th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 5th, 2012]

- Diabetes link to low testosterone [Last Updated On: November 25th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 5th, 2012]

- Testosterone Linked to Weight Loss in Obese Men [Last Updated On: January 2nd, 2018] [Originally Added On: May 11th, 2012]

- Testosterone may help weight loss [Last Updated On: November 25th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 11th, 2012]

- Testosterone-fuelled infantile males might be a product of Mom's behaviour [Last Updated On: December 25th, 2017] [Originally Added On: May 11th, 2012]

- Testosterone-fueled infantile males might be a product of Mom's behavior [Last Updated On: January 6th, 2018] [Originally Added On: May 11th, 2012]

- Testosterone supplements may help obese men lose weight [Last Updated On: January 5th, 2018] [Originally Added On: May 11th, 2012]

- Testosterone supplements 'can help men lose their middle-aged spread' [Last Updated On: November 25th, 2024] [Originally Added On: May 12th, 2012]

- Some doctors question safety of testosterone replacement therapy [Last Updated On: January 20th, 2018] [Originally Added On: May 15th, 2012]

- Health Canada Approves New Testosterone Topical Solution for Men [Last Updated On: May 15th, 2025] [Originally Added On: May 15th, 2012]

- Environment trumps genes in testosterone levels, study finds [Last Updated On: May 8th, 2025] [Originally Added On: May 15th, 2012]

- Global Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) Industry [Last Updated On: May 7th, 2025] [Originally Added On: May 21st, 2012]

- Testosterone Fuels Boom, Swindler Sows Panic: Top Business Books [Last Updated On: January 13th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 2nd, 2012]

- Increase in testosterone drug use [Last Updated On: April 12th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 4th, 2012]

- Testosterone Promotes Agression Automatically [Last Updated On: January 29th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 9th, 2012]

- Testosterone shown to help sexually frustrated women [Last Updated On: January 27th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 9th, 2012]

- Research and Markets: Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) - Global Strategic Business Report [Last Updated On: December 23rd, 2017] [Originally Added On: June 12th, 2012]

- Proposed testosterone testing of some female olympians challenged by Stanford scientists [Last Updated On: January 30th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 14th, 2012]

- Testosterone Makes Bosses Into Jerks, Says Paul Zak [Last Updated On: January 8th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 14th, 2012]

- Testosterone Therapy: A Misguided Approach to Erectile Dysfunction (ED) [Last Updated On: May 10th, 2025] [Originally Added On: June 20th, 2012]

- New drugs, new ways to target androgens in prostate cancer therapy [Last Updated On: January 8th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 20th, 2012]

- Long-term testosterone treatment for men results in reduced weight and waist size [Last Updated On: January 19th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 23rd, 2012]

- Declining testosterone levels in men not part of normal aging, study finds [Last Updated On: December 27th, 2017] [Originally Added On: June 23rd, 2012]

- Low testosterone not normal part of aging [Last Updated On: December 22nd, 2017] [Originally Added On: June 25th, 2012]

- Testosterone Does Not Necessarily Wane With Age [Last Updated On: December 6th, 2017] [Originally Added On: June 25th, 2012]

- Overweight men can boost low testosterone levels by losing weight [Last Updated On: December 10th, 2017] [Originally Added On: June 25th, 2012]

- Testosterone-replacement therapy improves symptoms of metabolic syndrome [Last Updated On: January 14th, 2018] [Originally Added On: June 26th, 2012]

- Testosterone therapy takes off pounds [Last Updated On: December 11th, 2017] [Originally Added On: June 26th, 2012]

- Weight loss may boost men's testosterone [Last Updated On: May 9th, 2025] [Originally Added On: June 27th, 2012]

- Low Testosterone? Study finds age may not be to blame [Last Updated On: May 12th, 2025] [Originally Added On: July 1st, 2012]

- Do you have low testosterone? [Last Updated On: December 15th, 2017] [Originally Added On: July 8th, 2012]

- Wall Streeters Buying Testosterone for an Edge [Last Updated On: May 11th, 2025] [Originally Added On: July 12th, 2012]

- Beefy Wall Street Traders rub on testosterone [Last Updated On: February 20th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 12th, 2012]

- Tale of two runners exposes flawed Olympic thinking [Last Updated On: December 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 19th, 2012]

- Genetic markers for testosterone and estrogen level regulation identified [Last Updated On: January 6th, 2018] [Originally Added On: July 20th, 2012]

- BUSM researchers identify genetic markers for testosterone, estrogen level regulation [Last Updated On: December 18th, 2017] [Originally Added On: July 20th, 2012]

- DRS. OZ AND ROIZEN: How to reap the benefits of normal testosterone levels [Last Updated On: December 23rd, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 21st, 2012]

- How Testosterone Drives History [Last Updated On: December 24th, 2024] [Originally Added On: July 22nd, 2012]

- Testosterone replacement is "fountain of youth" for men [Last Updated On: January 3rd, 2018] [Originally Added On: July 27th, 2012]

- Pill for low testosterone in men heads for phase II clinical trials [Last Updated On: December 31st, 2017] [Originally Added On: August 2nd, 2012]

Word Count: 1932